Choosing Land or Adapting Your Current Space

Choosing Land or Adapting Your Current Space

Your homesteading journey doesn’t start with a tractor—it starts with a plan. Whether you’re adapting a small urban lot or looking for 20 acres in the country, understanding the strengths and limits of your space is crucial. This section breaks down how to evaluate or find land that supports your long-term vision.

Set Clear Goals First

Before evaluating land or space, define your priorities. Research from ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture and University Extension Services, shows that homesteads fail or stall most often due to unclear goals—not lack of land. Write out what success looks like for you:

Do you want to produce 75% of your family’s food?

Are livestock part of your plan?

Will you sell products (eggs, vegetables, honey)?

Do you want to build off-grid infrastructure?

Are you looking for your homestead to be part-time or your long-term livelihood?

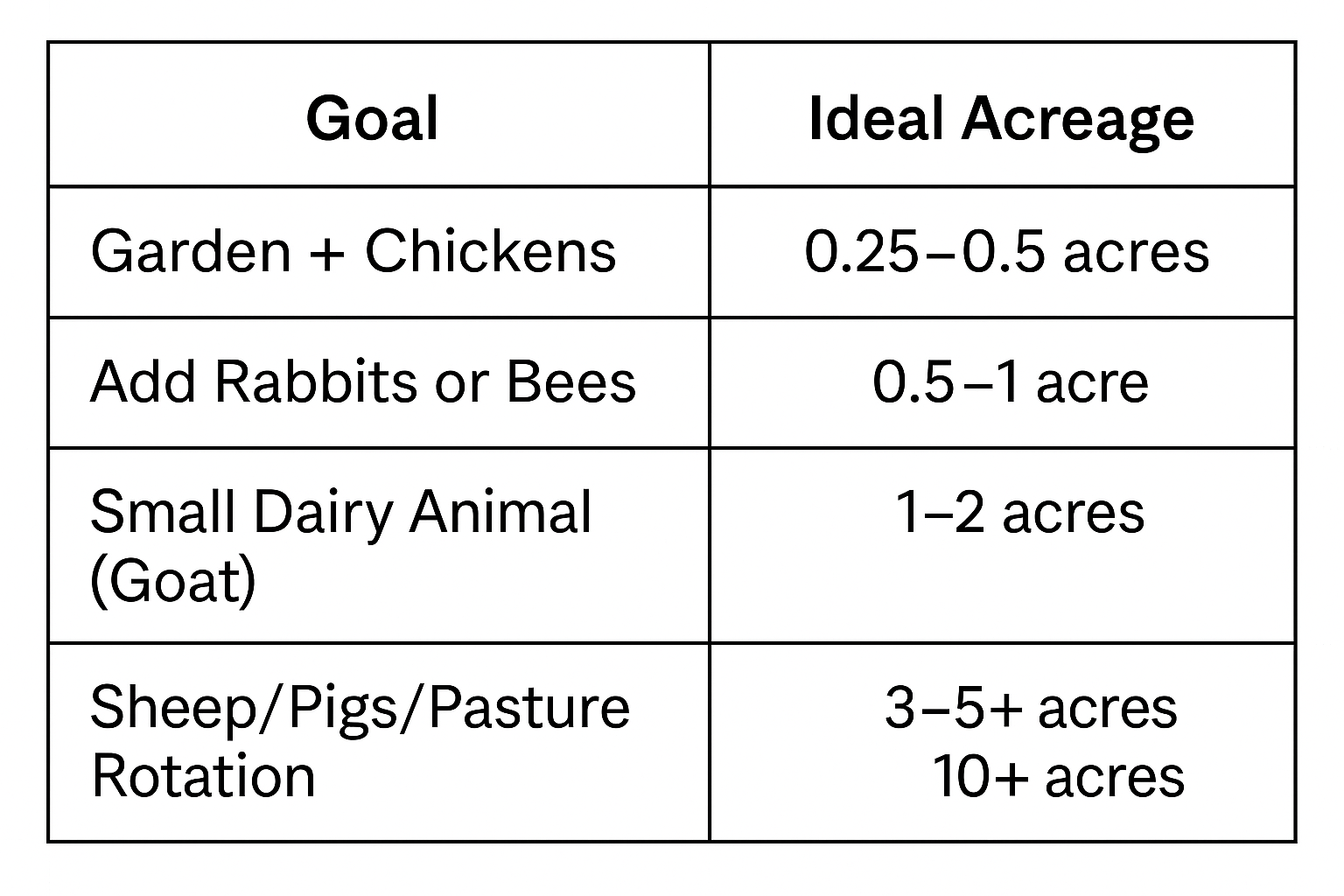

Your answers dictate how much land you’ll need—and what kinds of features matter most.

Adapting Your Current Property

More Americans are turning to suburban and urban homesteading. According to the USDA’s most recent survey of urban agriculture (2019), over 15% of small-scale food producers operate on less than 1 acre, many right in residential neighborhoods.

Core Factors to Assess:

Sunlight: Use apps like SunCalc or PlanMyGarden to map daily light patterns throughout the year. Fruit trees and most vegetables need 6–8 hours of full sun.

Soil: Test your soil through your state university extension office ($10–$25). Check pH, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and contamination (like lead in older neighborhoods). Raised beds or container growing can bypass poor soil.

Water Access: Many states regulate rainwater harvesting. It’s legal in all 50 states, but some (like Colorado) limit collection to 110 gallons and require it only be used for outdoor non-potable purposes. Check your local water code.

Zoning & Ordinances:

Livestock: Many cities allow up to 4–6 backyard hens but prohibit roosters. Rabbits are often treated as pets legally.

Outbuildings: Structures over 120–200 sq. ft. usually require a permit. In some states (e.g., Michigan), agricultural exemptions apply for rural zones.

Composting: Local regulations may have restrictions on where you can have compost piles, or prohibit composting meat, dairy, or pet waste.

If You’re Searching for Land

Let’s break down how to evaluate potential properties beyond the listing photos.

1. Zoning and Building Codes

Every county has a zoning map. Land may be zoned as:

Rural Residential (RR): Often allows a home, small livestock, and accessory structures.

Agricultural (AG): Ideal for homesteads. Fewer restrictions on animals, fencing, and structures.

Conservation or Protected Land: Often has environmental use limits.

Call the planning department, or check ordinances online, before buying. Don’t assume rural-looking land is unregulated, many areas require permits for everything from fencing to compost toilets. Also check into housing regulations if you are planning to build a house. I found most areas around me had a minimum requirement of square footage (average was 1,200 - 1,500 square feet) There are also requirements to hook up to utilities, such as city water, electric and sewage. These connections can become quite expensive

2. Water Availability

Water access is arguably more important than acreage.

Evaluate:

Well depth and flow rate (ideal: 5+ gallons/minute for household + livestock).

Rainfall patterns: Use NOAA climate data for your zip code. Areas under 30" annual rainfall will likely need supplemental water or storage tanks.

Permits: Some states, like Oregon and California, require a water rights permit to divert or store surface water—even for personal use.

3. Soil and Land Type

Request an NRCS soil survey (via Web Soil Survey). Look for:

Drainage class: Well-drained or moderately well-drained is ideal.

Soil type: Sandy loam is ideal for most crops.

Slope: Avoid steep slopes over 15%, which complicate building, erosion control, and equipment use.

Floodplain status: Use FEMA flood maps to determine whether any portion of the property lies within a designated flood zone. If it does, and you're financing through a federally backed mortgage, you may be legally required to carry flood insurance. Food risk can affect safety, future building plans, and resale value. Premiums for flood insurance can exceed $2,000 annually depending on risk classification and coverage.

4. Access & Rights

Road access: Ensure the land has deeded legal access, not just a gravel path across someone else’s property. Shared easements can lead to future conflicts with neighbors. I had a shared driveway with my neighbor, and the battle to get me to put in my own driveway began before I even moved in.

Easements: Ask for a title search. You don’t want to find out the utility company has the right to dig through your garden, or come through and cut out a 40' wide path through your trees.

Example: A coworker of mine had a natural gas pipeline running through his property that hadn’t been maintained for decades. When the gas company came through to reclaim the full right-of-way, they clear-cut dozens of mature trees, including several black walnuts. It was heartbreaking for him, but it worked out for me. I offered to process the logs on my sawmill in exchange for half the wood. It was a vivid reminder of why you need to check for existing easements, because even if nothing has happened for years, those rights can still be exercised, and the consequences can be dramatic.

5. Existing Infrastructure

A parcel with an existing well, septic system, electric hookup, and driveway can save you tens of thousands in startup costs. Barns and sheds in usable shape are a huge bonus.

Example: A basic permitted septic system can cost $10,000–$25,000 depending on soil type and tank size. A new well can add another $10,000–$30,000.

Red Flags and Hidden Costs

Other risks to watch for:

Environmental Restrictions: Wetlands, endangered species zones, or previous chemical use (herbicides, chemical storage) may limit development.

Power & Internet: If you’re working remotely or need refrigeration for livestock feed, verify connectivity. Satellite internet may be your only option in remote zones. When I purchased my property, all I could get at a reasonable rate was DSL, it was unbearable. Luckily, todays options are a lot more reasonable

Property Boundaries and Encroachments: Old fences or vague property lines can lead to disputes. Always get a professional survey before purchasing.

Fire Risk: In wildfire-prone areas, check local fire maps and requirements for defensible space around buildings.

Noise: Nearby highways, industrial operations, airports or gun ranges can become a real distraction form being able to enjoy your homestead

Illegal Dumping or Debris: Rural parcels are sometimes used for dumping. Walk the full lot, especially the back corners, for signs of buried trash, old tires, or hazardous waste.

How Much Land Do You Really Need?

Conclusion

Your homestead starts with where you build it, but also how you build it. Whether you’re retrofitting a backyard or evaluating raw acreage, what matters most is long-term sustainability. Focus on water, soil, sun, and access, and build your plan from the ground up. With intention, even a modest space can become a thriving homestead.